Critical Theory Goes Global

Universidade de São Paulo – HU Berlin. Joint research project:

"Critical Theory Goes Global:" Transfers, (Mis-)Understandings and Perceptions since 1960 - Joint workshop April 12th/13th 2018 at HU Berlin (workshop program)

“Critical Theory Goes Global”: Latin America in Focus - 2nd Interdisciplinary Workshop June 13th/ 14th, 2019 at the Department of Philosophy, University of São Paulo (Workshop program)

Principal Investigators:

Rahel Jaeggi: Institut für Philosophie (Philosophy) – HU Berlin

Rurion Melo: Departamento de Ciência Política (Political Sciences) – Universidade de São Paulo

Luiz Repa: Departamento de Filosofia (Philosophy) – Universidade de São Paulo

Nenad Stefanov: Interdisciplinary Center for Border Research (History) – HU Berlin

Background and Ideas

In light of the critique of universalist approaches in the last two decades by cultural and post-colonial studies, on the one hand, and the growth of anti-democratic ethnonational particularist movements, on the other, a reexamination of universalist, cosmopolitan philosophical concepts and methodologies has acquired renewed relevance.

At first glance, especially concerning the critique of Eurocentrism, classical universalism might be seen as – paraphrasing Dipesh Chakrabarty from a different but familiar context – “inadequate but indispensable”. Chakrabarty’s critique of Eurocentrism makes sense insofar as it exposes the particularism concealed behind such forms of false universalism. The question arises, though, whether or not his Heideggerian inspired abandonment of universalism as such is justified? We think that the concept of a non-Eurocentric universalism is still worth exploring as an alternative to post-modern and post-colonial cultural relativism.

At first glance, especially concerning the critique of Eurocentrism, classical universalism might be seen as – paraphrasing Dipesh Chakrabarty from a different but familiar context – “inadequate but indispensable”. Chakrabarty’s critique of Eurocentrism makes sense insofar as it exposes the particularism concealed behind such forms of false universalism. The question arises, though, whether or not his Heideggerian inspired abandonment of universalism as such is justified? We think that the concept of a non-Eurocentric universalism is still worth exploring as an alternative to post-modern and post-colonial cultural relativism.

In order to elaborate the possibilities of a reformulated universalist critical theory of society, and to reflect on both its inadequacies and indispensability, is seems promising to focus on the transfer, adaptation and modification of ideas in different social and historical contexts.

The tensions that exist between universalist concepts and methodologies, on the one hand, and the development of social and cultural theory in different geographical and historical contexts, on the other, is paradigmatically exemplified in the international reception of the Frankfurt School. Its Critical Theory -- to put it briefly -- is characterized by the attempt not only to maintain the idea of universal emancipation regardless of ethnic, confessional etc. specificities, but also to take seriously the historically specific social conditions that have shaped politics, culture and psychological character structures in particular contexts.

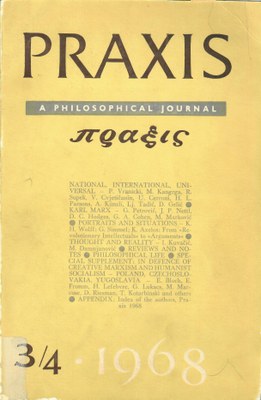

It is remarkable that Frankfurt School Critical Theory has encountered such lively and enduring interest not only in Western Europe and the US, but also in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia and the Middle East. In regard to Eastern Europe, in particular, there has been a diffusion of these ideas since the early sixties in countries before and after the Cold War.

But it is not merely diffusion. It is too simple to think about this process in categories of an active transmitter and a passive recipient. Therefore the project will focus on the possibilities and the limitations of such transfers of ideas. Some questions that are of interest: in the process of reception have specific concepts and methods been adopted in their original form, or does it make more sense to speak of modifications? What role did such transfers play on both sides? What were the specific social and political conditions that stimulated such a reception? To what extent did the participants on both sides of these transfers develop an understanding of the social and political conditions of their interlocutors from other countries and regions? How did these conditions shape this reception and – conversely – what can we learn from it today as historians about the changing social and political conditions that existed in these different places?

Concerning the periodization of the project, it will concentrate on the last four decades of the twentieth century, which were characterized by deep social and historical transformations. Four distinct periods are visible: the culmination of the “Golden Age” or “Affluent Society” in the 1960s; the economic downturn and the emergence of “post-industrial societies” in West in the 1970s; the return of ethno-nationalism, the rise of neo-liberal globalization and the collapse of “real-socialism” in the 1980s; and, finally, the acceleration of neo-liberal globalization and the transformation of Eastern Europe societies, either by rapid adaption to the West, or – as was the case in Yugoslavia – a decent into war. Of course this periodization is Eurocentric, but it can serve as a point of departure for our research. One of our aims will be to see how a closer study of the international reception of Critical Theory makes it necessary to revise and reformulate such a periodization, or if the very idea of universal historical periodization needs to be reconsidered.

The case of the reception of Critical Theory in Brazil shows that is necessary to change the historical references or at least to add very different elements in comparison to Europe. Between the 1960s and 1990s, this reception was strongly marked by the historical context of the military dictatorship (1964-1985) and by the process of redemocratization (from 1985 onwards). The first translations of the classic authors of Critical Theory (Benjamin, Marcuse and Adorno) were published in the mid-1960s, precisely at the time of the military coup. Despite political repression, it was possible to increase in a significant way the translations of these and other authors in subsequent years.

It is interesting to note that the most important fields of application of Critical Theory by Brazilian intellectuals during this long period were those of the critique of culture, literary criticism and mass communication, on the one hand, and the theory of democracy and social movements, on the other. These uses coincide with changes in political reality. In the period of the military dictatorship, the use of the categories of Critical Theory focused mainly on cultural criticism, either to theorize with Benjamin (and Brecht) engaged art, or to think with Adorno and Marcuse about the processes of domination through cultural industry and the injunctions of industrial society.

This field of application did continue in the years of redemocratization, but it was supplemented thereafter with an increasing interest in social theory and the theory of social movements and the public sphere. Here the focus was mainly on Jürgen Habermas and, more recently, Axel Honneth.

Left political experiences, such as new democratic forms of participation, were thought from Habermasian categories such as communicative action and discourse. At the end of the 1990s, this experience was consolidated in terms of theoretical research with the creation of a research group on “Law and Democracy” at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning, which is coordinated by Ricardo Terra (Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sao Paulo) and Marcos Nobre (Professor of Philosophy at the University of Campinas).